Virtual First Primary Care

One of the biggest problems in American healthcare (besides cost) is the shortage of providers. From physicians to nurses to mental health professionals, it’s getting dire at every step — from finding a provider when you need one, to being able to make an appointment in a reasonable timeframe, to getting the treatment you need near where you live.

One of the most promising solutions is virtual care. It’s efficient, it keeps sick people out of public spaces, it addresses localized provider shortages, and it’s good business for healthcare — better access for more patients also means more patients seen and paying (let’s be honest, it is a business).

There’s at least one big barrier: A majority of patients still believe they have to see their doctor in person to get good care, even if it’s inconvenient and difficult for the simplest of conditions, like ear infections or dermatitis.

The truth is, about 80% of visits — particularly for common conditions treated by primary care, the entry point for all care in any health system — can easily be virtual.

No one needs to work that hard to get care or see patients.

Enter, virtual first primary care:

2-3 days virtual, 2 days in-person appointments

Primary care plus support for chronic conditions, like diabetes or obesity

Staffed to address more holistic patient needs than typical PCP clinics

Shorter appointments —> higher availability

Use of patient-facing technology to streamline every visit

In practice, this supports:

Faster, more complete understanding by staff of what’s happening for patients, achieved by standards for consistency that support a cross-disciplinary care team

Chronic conditions treated in one clinic instead of through several specialist referrals, unlocked by having pharmacists, social workers, and eventually other specialists like mental health providers on staff.

Streamlined appointments focused on time with a patient, achieved by using patient-facing tech for tasks like check in, reason for visit, and check out

What I did

I had the benefit of working with a physician who was running a pilot of this model, so we were scaling and enhancing an existing operational model.

These included maximizing the use of electronic forms and patient onboarding so that 15-minute appointments could be spent providing care, not typing; SLAs in place for 4-hour or less response time to patient messaging; more modern clinics that had the ability to support patient-friendly technology; and better technology support for patients whose visits were mostly virtual.

So, in a way, designing this as a scalable service was pretty easy. In a whole other way, I had to work with some pretty squirrelly technology — Epic, the relative standard for electronic health records and its patient-facing view, MyChart.

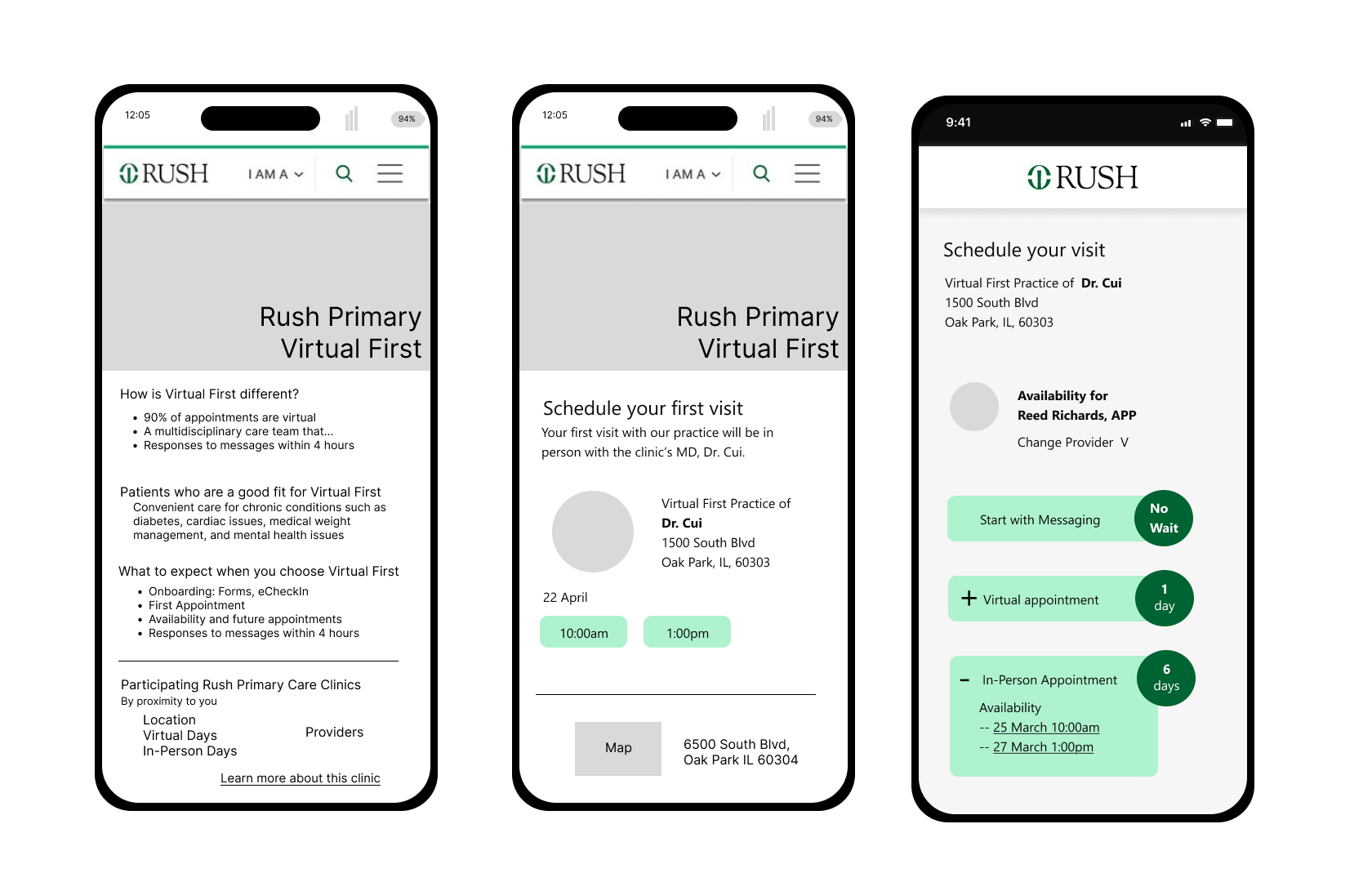

I designed a prototype to share with the full team after running an ideation workshop. (Screen shot below. More could be shared in an interview.)

I socialized it with everyone who needed to buy in, including the IT team. When I departed they were building out the operational model and technical requirements.

How I did it

So many people have experience with the weirdness of MyChart that I won’t describe it all (also it would be a novel), but let me just say this: most of its weirdness is tied to operational inconsistency across provider practices.

Such a mouthful, so in plain English: doctors who set up their practices want to do it their way, and system IT teams typically bend over backwards creating customizations for them. This creates a big mess when you start looking to improve the entire system. And then there’s Epic, which is even weirder.

I had to learn a lot about both systems to design this as a scalable service. I also had to lean pretty hard on the technology team responsible for the current state; I’m reasonably certain they didn’t know why they should work with me at all, when to them, this looked like just another clinic.

Conclusion

Healthcare and its delivery in the United States is one of the most inhumane systems I have ever come across, which may seem an odd conclusion when this work was setting out to improve things for both providers and patients and has a pretty decent model to achieve that goal, at least on a small scale.

What I mean is this: for a system that is supposed to be about providing human beings with care provided by other human beings, it is not built to support either set of human beings.

I visualize it as the monolith in 2001, but bigger, standing between both provider and patient as a behemoth set of barriers, including

linear protocols for diagnosing patients based on symptoms that don’t leave room for listening compassionately and treating holistically, making providers seem like automatons speaking a different language

a business model that incentivizes quantity when its users (patients) need quality, while providers may well prefer to focus on giving higher quality care to fewer patients

regulatory requirements that are well-intentioned but create a bureaucratic maze worthy of Kafka, and

extractive, exclusive health insurance (in the US)

financial barriers for patients, who bear the cost of a system that is so expensive to run

Three phone screen sketches of the public-facing content about a Virtual First Primary Care Clinic.