What you’ll find here

A long-ish career that spans many roles, industries and sectors = a lot of material to work with.

But no one wants to read that novel. Not even me, really. So, these are brief stories about some of the work I’ve done since 2012.

A bunch of DocuSign — Perspective, work and impact on career ladders/hiring, design maturity, and enterprise-level facilitation.

Splash of Rush — While I wouldn’t say I did design work, this is a design-sh stroy about virtual care delivery.

Sprinkle of Avanade — about rapidly scaling a team to over 100 people in a design operations role.

Spoonful of MorningStar — how I approach designing services (Accessible Investing) and products (Modern Portfolio Theory), yes, including some UX deliverables I created.

Building a global design team

When I started in 2010, we had more creative directors than designers.

There were two designers in Australia, four in Buenos Aires, and regional creative directors in the US, Sweden, and Australia.

The VP who hired us had successfully made the case for incubating a creative capability, after gathering data that told him 40% of their deals were lost because they didn’t have an in-house design team.

Time and time again in pitches, prospective clients asked for design to be part of the team, not an add-on with an expensive agency that didn’t understand the tech and would deliver unworkable designs.

What I did

Built credibility with pitch work

Enabled and directly supported growth from 6 to 100+

Supported strategic growth plans for the global practice

Operationalized design in the consultant force

Building credibility and growing the team

At first, we had creative directors essentially zipping all over the world trying to find work to elbow their way into. Every now and then they would score and get more involved in a pitch. I would coordinate creative explorations with designers, the Creative Directors would clean up slides, then use exploration work to do the storytelling needed. It worked — we were winning deals, much bigger deals. People started asking for the creative directors to participate.

This is when my work kicked into high gear, because I was there to help the team get organized and coordinate.

I saw the need to create a flow of information between team members that didn’t involve me personally translating everything for everyone. Complicating this effort, we worked across time zones that were not friendly to doing this easily.

I created and refined async tools so that work got done and met expectations. (Guess what we didn’t have? Slack.)

I did that just in time, because now we needed to scale to actually do the work we had proposed. I persuaded our VP to let me hire ahead of demand for the work I could show was coming to us.

Our hiring efforts went so well that we ended up with 100+ designers.

Seventy-five of them were in Buenos Aires. Everything from making sure teams had offices with places to take client conference calls, to supporting team members in gaining confidence to be on those calls, to making sure they all had the right licenses, and managing workflow globally, fell to me. It took a while, but I was able to gain the team’s trust that I would deliver improvements to their work environment and we could run a smooth shop.

Zoom In

A small example of the things I worked on: licensing software. Early on, when we had about 15 designers on the Buenos Aires team, there was an unexplained slowdown in velocity. When I asked about it I found out that they were all sharing a Photoshop license. (Also: No Sketch or Figma yet.)

So I went to our VP… who asked if Photoshop was really necessary because it was expensive, and wanted me to investigate if the team could “just use MS Paint.” Aha! Now I knew why license requests had not been made.

A second operational effort I took care of was career ladders, because hiring was continually on the struggle bus without it. Our job titles were for developers and we didn’t have a way to talk about career planning with our teams or candidates.

So I found the right person, got a crash course in career ladders from HR, and built out the first of three comprehensive career ladders I would build in my career for information architecture, visual design and user experience.

Third, I had to sort out our engagement model.

With our teams working in remote locations, and the way creative work happened in bursts followed by a lot of waiting, the “butt-in-seat” model of tying a name to a contract and location wasn’t going to work.

We needed work to flow around the studio so that one person wasn’t over-allocated while others sat around and waited for something to do.

I had to make the case that we could not attach names to deals or project plans in estimates or contracts, which was the typical practice, and the project team would start out working through me to move the work to design teams.

This was not scalable, as you can imagine, so I had to delegate pretty quickly once the pitches were won and deals signed.

Finally, we had skill bias issues show up. I was doing a regular check-in on how projects were going when a designer told me about the 6-hour phone calls he had been on for the last month to support developers rebuilding from scratch something he already delivered three weeks prior.

SharePoint sites at the time ran off of something called a “master page” which was really just UI display styles.

Developers across multiple projects were straight up not using the ones we were delivering.

(Honestly, they were glorified style sheets. I still don’t see why it had to be so hard.)

It turned out they didn’t believe a design team from Argentina could do that work.

While I would have loved to declare “you’re biased” and have that fix it, I had to demonstrate the efficiency and budget hits project teams were taking because of this behavior. It was pretty easy.

Strategic growth and operationalization

Now that we were popular and growing, it was time to start looking at moving through the last incubation gate and becoming a “real team.” In 2011 the leaders got together in person to come up with how we would do just that.

Two items in our plan fell to me — revenue recognition for deals we helped sell and getting estimates automatically included so we didn’t have to negotiate scope twice for each project.

The thing about working remotely for a 10,000-person organization is that you have to know how to find people. I had to figure out who had all the sales tracking spreadsheets, and then I had to find the person who owned our estimating model. That took about a month.

For sales support, first I had to get us included at all in the documentation for sales, which took about three months. Then, to get a number that didn’t look like double-dipping on claimed revenue, I had to make a case for what our share should be. I was able to figure that out and persuade the Keeper of the Spreadsheets to have a column for XD added. This got us on the way to being a profit center of our own, so that once we moved out of incubation, we could continue to hire ahead of demand based on revenue we generated for deals that would become projects.

Then there was the estimating model, a gargantuan spreadsheet. Once I found the right guy somewhere in Australia, I had to explain that our work could not be back-figured based on a percentage of engineering, and that we needed both exploration and production time in our estimates, so no, 4 hours for a complete set of wireframes and 8 hours for detailed design was not going to cut it.

Two months later, our estimates were included in every deal we helped pitch and win, all over the world. This grew our footprint and our revenue.

Summary of what I learned

Do you ever look at a piece like this after you’re done writing it and think, “Wow. I did a lot of things”? That’s what I think about this one.

If you read the whole thing, you probably noticed that I spent a lot of time anticipating needs and saw the phrase “make a case” quite a bit, and that’s really my point in telling this story.

Most of scaling a team and getting it to a self-sustaining, growing profit center in this context is about seeing what’s coming and being able to build a case for what the team will need soon (but preferably not right now).

I had to learn how to make a business case for everything from decent office space to flexible workflows for a completely new organizational function. It took quite a bit more groundwork and storytelling than, say, arguing for a new developer certification.

And while I definitely had support and guidance from our VP, our creative directors were much too busy to manage anything I was doing. It was not the first or last time someone who had not worked in design would be my direct manager.

Being able to do what I did for this team takes good instincts for building a business and strong creative problem-solving muscles I still use today.

Modern Portfolio Theory FTW

40 years ago, the mutual fund was a relatively new thing. It was this amazing way to diversify your investments, to spread risk, which is what all good investment professionals will tell you: never put all your eggs in one basket.

But… who picks those eggs, and how?

Enter Morningstar, which built revolutionary tools and data visualization around the mutual fund. One such revolutionary tool was called Portfolio Builder.

Portfolio Builder lets you choose individual stocks, look at their fundamentals, past performance, and other factors, and add them to a collection voila! You built your own model portfolio (not exactly a mutual fund, but close). If you were really good at stock picking, that portfolio did amazing. Go, you! Then you get to maintain it, rebalancing and choosing new stocks forever!

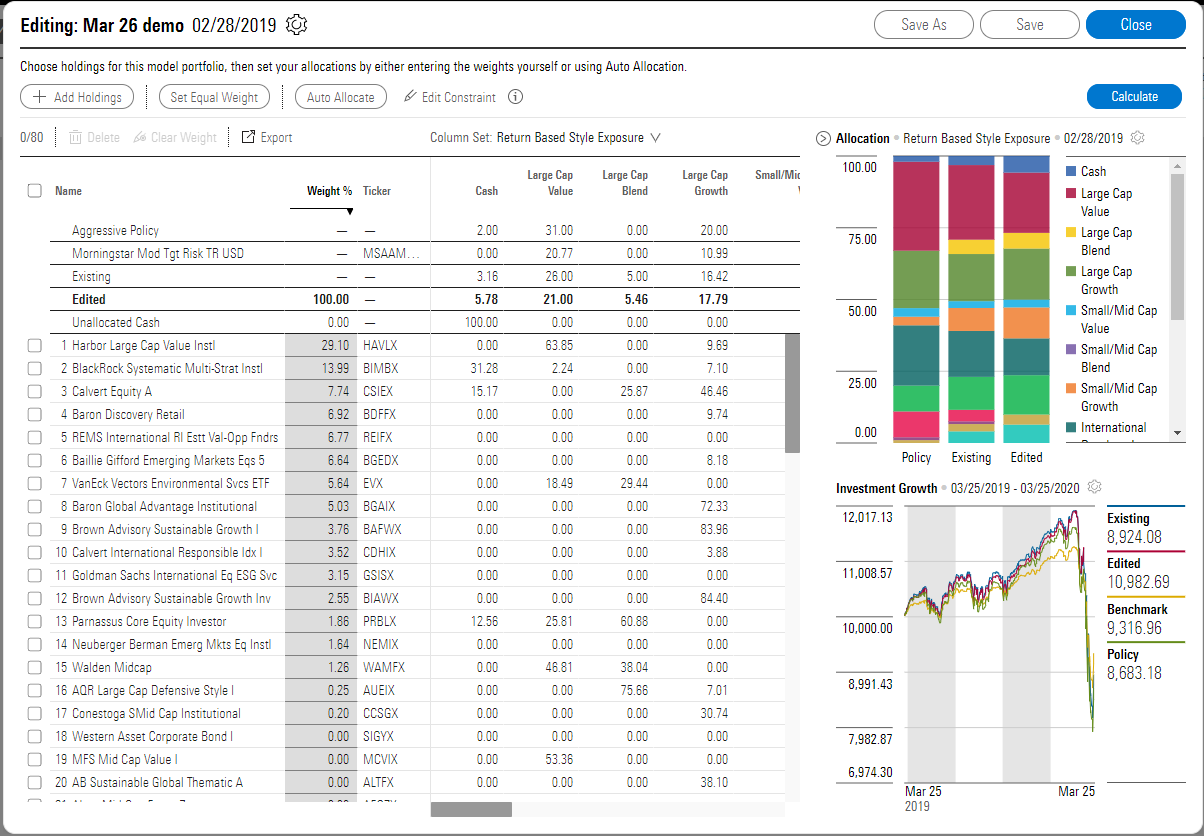

Here’s what it looked like:

A highly complex mutual fund portfolio tool

(Did I mention I started this work in February 2020?)

The most helpful part of the tool was the Allocation modeling at the top right, because it told you what sectors and categories you were adding and how they were balanced.

Fast forward forty years, and no one does it like this any more.

This was the challenge laid before me by the CPO — what would we need to do to bring Portfolio Builder up to date?

As I soon found out, the problem is no one does it like this any more.

In fact, the inverse is true of the process. Here’s what happens:

Model portfolio builders set up industry segments they want to add to their portfolio, like large cap, energy, and other criteria. They add return parameters like ESG rating, risk tolerance, and other factors like Sharpe, and they run a query against a database of stock performance which spits out what should be in your portfolio, how much, etc.

Basically, auto-balancing without human choice. It’s cleaner and better. It’s one way AI and machine learning can actually benefit investors.

People use a variety of tools to do this.

At Morningstar, analysts were using a monstrously slow Excel spreadsheet to build them. (Not the Portfolio Builder. When I asked, I heard “why would I do that?” a lot.)

So I set about designing what a portfolio builder would have to be able to do to adapt to new processes.

I had to deeply understand the factors involved in building a new model portfolio, how they affected one another, and how decisions got made by analysts to design this tool.

What did that look like? At the end of putting in all of your variables, it delivered this:

All along the way, the CPO was pleased with the work. It was clear I understood the problem and the design was graceful, it tested well, everyone understood how I was laying out performance and factors, etc.

But when he asked me what the plan was to make our current portfolio builder into this, I said what I had discovered by talking to the product owner: “we can use the data, but we can’t use the flows, UI or current backend code.”

Which infuriated him and surprised me. After all, I laid out the progress the entire way. Nothing was a surprise.

I drew out the two flows that worked in reverse of one another: the old process was about building something from nothing, while the newer way was a process of elimination, working backward from a universe of all mutual funds and stocks.

Sad Trombone

I left Morningstar a month later.

It was not the first or last time I’ve been told that an organization was not ready for my level of innovation work even though I was explicitly hired to do just that.

To some, that will look like a failure as a designer. I should have been able to persuade! Convince! Succeed! Spin up a new team! Get an investment!

Find a way to make Portfolio Builder work!

In that way, this is not a good piece of product design work, because there is no product at the end to show for it. Innovation that goes nowhere isn’t a success.

But… you want to know if I can redesign a current product that meets user needs in a hands-on way. Now you do. If there had been investment, I could have led the redesign easily. It was a proven idea, a proven flow.

Post Script

I found out much later that Morningstar is littered with ideas like mine, designs that were tested and valid but couldn’t be built without a serious reconsideration of the current technology. You have to have an appetite to do that in the c-suite.

It doesn’t fit with big bang quarterly announcements for a public company.

I also like to think that someday, someone will disambiguate the tech stack from the data that underpins it. Morningstar already sells its data to companies that have done just that.

—The End—